Herbivore Digestive Processes

This Herbivore page explores the digestive processes of both cows and rabbits, two different types of herbivores. It is helpful for rabbit owners and breeders to better understand how the rabbit's digestive tract works.

(Advisory to readers: the content on this page does contain photos of animal anatomy in the interest of scientific accuracy. Some people may find these images disturbing. The animals in the photos were treated with dignity and respect in life, then culled using quick and humane methods to spare the animal physical and emotional suffering.)

But additionally, it is important that a website advocating the eating of meat (including rabbits) provide the evidence for humanity's physiological need to eat animal based nutrition for health and survival. Therefore we'll also contrast plant-eater digestive processes with those of humans.

It's all there and evident in the differences in basic biology. If you're unsure about the ethics of eating meat (including rabbits), we hope this info will help.

Plant eaters come in two types:

- Ruminants with a multiple-chambered stomach (also described as two or more stomachs)

- Mono-gastric non-ruminants -- herbivores with a single stomach that don't chew the cud

Both types obtain 100% of their food from plant forages. But unlike

humans, both types of herbivores gain a significant part of their nutrition

directly from the digestion of billions of bacteria inhabiting their one or

more stomachs. Here is how they obtain that extra nutrition.

Ruminants (i.e. cows, sheep, goats) have four stomachs and chew their cud. (Take a look at Carnivore Digestive System for a refresher on the anatomy of the cow's digestive system. No, cows aren't carnivores.)

The bacterial counts

in a cow’s first 3 stomachs are astronomical. No digestion occurs in these

first three stomachs, so the bacteria there can keep right on multiplying and

feasting on cellulose. The bacteria are an

essential part of the cow’s ability to eat only plant matter, as the bacteria

breaks the cellulose down into easily digestible carbs that both the cow and the bacteria and other microbes can utilize for nourishment.

To increase their digestive effectiveness, ruminants regurgitate what they just ate into their mouths and chew their cud whenever they are not actively foraging. This provides prolonged opportunity for the cow to grind the plant matter into ever tinier pieces to improve the ability of the bacteria to digest the cellulose.

When

stomach #3 finally empties into stomach #4 for the actual digestion, it

delivers up its billions upon billions of bacteria to digestive acids and

enzymes, which kill and break down the bacteria. Cows gain a cornucopia of bacterial

(non-plant) nutrients, including protein and the elusive B12, from these many

kilograms of bacteria.

Alfalfa Cubes, Timothy Hay, Orchard Hay (#ad)

Rabbit Digestive Processes

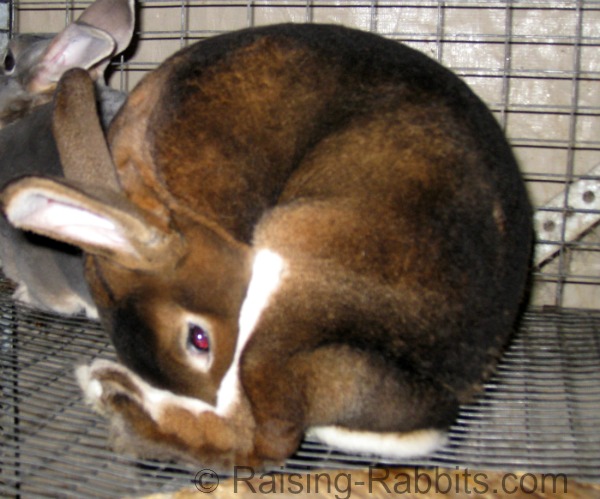

Rabbits are mono-gastric non-ruminant herbivores. They have one stomach, and a single large chamber toward the end of the digestive tract called the cecum, or hind gut. (See below.)

Rabbits don’t chew the cud, but they do send their food through their intestinal tract twice using a completely different mechanism than that of cows and some other herbivores.

On the first

transit through a rabbit's guts, food matter travels the length of the small intestine, finally arriving

in the rabbit’s cecum, or hind gut. The cecum is a blind pouch twice or three

times the size of the stomach and situated at the junction of the small and

large intestines. The cecum holds the rabbit’s enormous population of healthy

gut bacteria that break down all the cellulose and fibrous plant material. Within the cecum, muscle action

segregates the heavy, low-nutrient fiber from the high-nutrient, bacteria-laden,

digesta. The fiber then becomes

concentrated and shuffled off into the colon, where it ends up defecated as the

familiar hard round droppings.

(Pictured: A rabbit's intestinal tract separated for better visualization.)

- Top: Stomach

- Left:

The tangle of small tubes are the small intestines that connect the

stomach to the large blind pouch which is the cecum.

- Right: At the

end of the small intestines is the very large cecum. This is the organ

that holds the huge population of digestive bacteria. At the same spot

where the small intestine connects is also the connection to the large

intestines.

- Bottom: The

large intestine, or colon. In this rabbit, the hard round pellets are

lined up for exit. The rectum, anus and tail are attached.

Cecotropes

CecotropesWhen this process is concluded, the remaining highly nutritious contents of the cecum travel from the cecum to the colon. The soft cecal contents get segregated into quarter-inch soft little "marbles," wrapped individually in a mucus membrane and then collected together into mushy, raspberry-shaped “cecotropes.” Cecotropes get a second transit through the rabbit’s intestinal tract.

As though a switch was thrown, cecotrope after soft cecotrope now pass single file down the colon to the anus. The rabbit puts its nose to its privates and eats these soft cecotropes directly from its anus, swallowing them whole. (Humans: don’t try this at home!)

Cecotropes contain high levels of Vitamin K, B-vitamins including B12, bacterial protein and bacterial nutrients, magnesium, calcium, phosphorus, iron, chloride, sodium and potassium.

(Pictured: A rabbit stomach is cut open to reveal that it is almost entirely full of ingested cecotropes which have been swallowed whole.)

Bacterial protein content in the cecotropes as a percentage of the total consumed protein ranges between 30% and 68%, depending on the quality of the rabbit’s feed or forages. The ability of the rabbit to recycle its cecum contents and gain nutrition from the bacteria in its cecotropes is known to help correct nutritional shortfalls of various forages.

Does the Human Digestive Process Really Function Like an Herbivore's?

I ask, because I've heard from folks that insist humans are mono-gastric herbivores.

Now that we've looked at the digestive processes of mono-gastric herbivore rabbits, what do you say? Do you know any humans that send their digestive tract contents back through the digestive process a second time, via either the top end or the hind end?

- No humans alive today have massive, blind-pouch

hindguts as do mono-gastric herbivores such as rabbits. No one confuses our itty bitty appendix

for a hindgut, and everyone acknowledges that no digestion occurs in a human

appendix.

- Nor, for the record, are there any humans with three bacteria-filled stomachs, along with a fourth stomach in which digestion takes place.

- No human being chews the cud. There is no nutritional advantage

to a human to retch up the stomach contents into the mouth. In fact, due to the potent

hydrochloric acid in vomit, repeated retching, re-chewing and re-swallowing would

certainly damage the mouth and esophageal linings. (Not to mention tasting absolutely horrid.)

- Humans have no reason to practice

coprophagy (the eating of feces that is normal behavior among many animals, according to the Merriam Webster dictionary). In fact, such a practice could be fatal. What ends up at the far end of the

human digestive tract is known as waste for a reason – the good has already

been extracted from it. The germs in our guts, such as E. coli, belong there and not in our mouths. E. coli has

killed humans who ate contaminated foods.

- Unlike rabbits and cows, human colon bacteria do not participate in digestion at all. The human digestive system is very nearly

sterile from the stomach to the large intestine, or should be. Any B12 that colon bacteria manufacture is not available to humans.

- Unlike rabbits and cows, the human digestive system has no enzyme, and no other mechanism for breaking down the very complex cellulose and hemicellulose molecules found in plant cell walls. We gain no nutrition whatsoever from either

type of cellulose.

- Unlike rabbits and cows, humans have no intrinsic source of vitamin B12 should they choose to eat a vegan diet. Because plants offer no bioavailable vitamin B12, and without the ability to access and digest many pounds of bacteria as do herbivores, humans on a plants-only diet will

eventually (after several years) sink into a vitamin B12 deficiency if they fail to take B12 supplements or eat

foods that are artificially fortified with B12.

- Especially notice that eating "dirty" vegetables will in no way satisfy a human's B12 needs. Nor does this satisfy the B12 needs of either ruminants or non-ruminants. It requires literally many pounds or kilos of bacteria digested along with the contents of the fourth stomach chamber (in cows) or cecotropes (in rabbits) to supply herbivores with the needed B12, Vitamin A, essential fatty acids, and other bacterial nutrients such as protein.

These are profound differences between humans (omnivores), and true herbivores.

Armies of bacteria are active participants in an herbivore’s digestive processes, and then whole regiments of those armies are killed and digested by their plant eater hosts. Humans will never get that advantage.

When you look at it that way, herbivores are not truly vegan after all, despite eating only plants.

See Carnivore Digestive System for a comparison of the anatomy of ruminants (cows), non-ruminants (rabbits), carnivores (dogs), and omnivore (humans).

See Vitamin B12 Deficiency to better understand the role of Vitamin B12 and its absence in plants.

These Two Complimentary Books Will Answer Virtually ALL Your Questions (#ad)

Sources:

- http://www.stevepavlina.com/forums/health-fitness/487-vegan-sources-vitamin-b12.html#post3750

- http://freeradicalfederation.com/VitaminB12inPlantFoods

- http://www.vrg.org/nutrition/b12.htm

- http://articles.mercola.com/sites/articles/archive/2011/04/11/how-moms-vegan-diet-unintentionally-killed-her-innocent-child.aspx

- http://www.chelseagreen.com/content/cultural-rehabilitation-the-health-benefits-of-fermented-foods/

- http://www.rawfoodexplained.com/fermented-foods/the-harmful-effects-of-fermented-foods.html

- http://www.veganhealth.org/b12/plant

- http://www.stevepavlina.com/blog/2005/09/are-humans-carnivores-or-herbivores-2/

- http://www.rawstory.com/rs/2012/04/02/scientists-find-clue-to-human-evolutions-burning-question/

- http://gostudyinaustralia.wordpress.com/2011/04/06/rabbits-the-surprisingly-interesting-tail-of-this-invasive-species/

- https://www.raising-rabbits.com/carnivore-digestive-system.html

- http://www.healthaliciousness.com/articles/Top-5-Natural-Vegetarian-sources-Vitamin-B12.php

- http://www.umm.edu/altmed/articles/brewers-yeast-000288.htm

- http://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminB12-HealthProfessional/

- http://nutritiondiva.quickanddirtytips.com/nutritional-yeast-good-for-you.aspx

- http://www.veganhealth.org/b12/vegansources

- http://lesaffre-yeast.com/five-steps.html

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marmite

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vegemite

- Nutrition of the Rabbit, 2nd Edition, Edited by Carlos de Blas and Julian Wiseman

- http://shinysatins.weebly.com/rabbit-overpopulation.html

- http://www.healthaliciousness.com/articles/foods-high-in-vitamin-B12.php#8sxLvkCHI4lYDAMS.99

- http://www.happycow.net/vegetarian_diet.html

- The Private Life of the Rabbit, by RM Lockley

Double-Value Guarantee

Our policy is to always OVER-deliver

on value,

which is why your purchase is fully covered by our

Double-Value

Guarantee.

Go ahead - take any of our e-books for a test drive. Peruse our detailed informational and educational e-books. Examine our plans for building rabbit cages, runs, or metal or PVC hutch frames. Check out the Rabbit Husbandry info e-books.

If you aren't completely satisfied that your e-book purchase is worth at least double, triple or even quadruple the price you paid, just drop us a note within 45 days, and we'll refund you the entire cost. That's our Double-Value Guarantee.

Note: When you purchase your

e-books, they will be in PDF format, so you can download them to any device that

supports PDF format. We advise making a back-up copy to a drive or cloud

account. If the books are lost, you can also purchase another copy from Raising-Rabbits.

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.